Cyberwarfare targeting the energy sector. Is Europe under threat?

By Cluster25 Threat Intel Team

May 27, 2022

The energy sector is a pivotal one for the whole contemporary economy. A disrupt of its functions could cause huge problems for the economy of a certain country.

In this report C25 listed some of the most famous cases of disruption that affected the energy sector and their consequences.

INSIGHTS

Critical infrastructure consists of an asset, system, or element necessary for guaranteeing essential societal functions like economic growth, national security, as well as public health and safety. Disruption or destruction of which would have a significant, if not catastrophic, impact on those functions.

Typically, the sectors involved are water, transportation, Information, communication technology (ICT), and energy. These systems are often connected or interdependent with one another. For example, the energy sector relies on transportation for fuel delivery, water for electricity generation, and telecom for control and operation of infrastructure, and conversely, it provides essential power and fuel to stakeholders in those sectors.

The energy sector has three primary interconnected sections: electricity, oil, and natural gas. Their assets are geographically dispersed and connected by systems and networks owned by both private sector entities and all levels of government.

Critical Energy Infrastructure (CEI) is vulnerable to various types of attacks and increasingly to cyber threats that seek to compromise security, public safety, and economic sectors. Energy is an integral part of all sectors of the economy and social sphere, it plays a special role in ensuring the security of the development of modern society. Therefore, energy infrastructure has become an essential part of the concept of hybrid warfare. An example of direct attacks on CEI can be found in Ukraine.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine continues, the world now understanding what the battlefield looks like: a mix of conventional and unconventional tactics, bullets and malware, soldiers and hackers working together to achieve their goals, in different ways but coordinated toward a common mission.

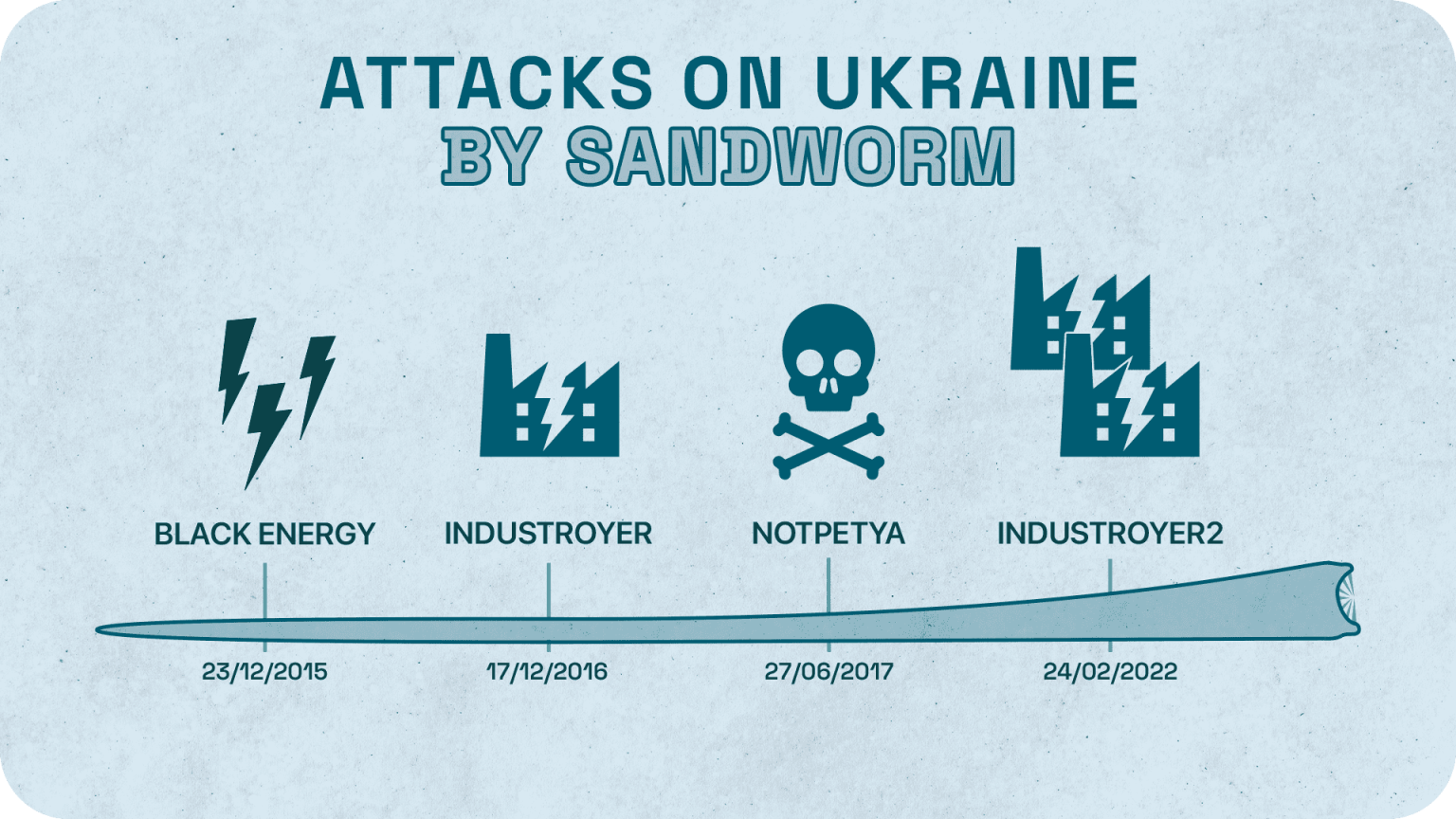

7 years ago, in a first-of-its-kind attack, hackers managed to wreak havoc on an entire region by cutting off the power in many homes. On the afternoon of the December 23, 2015 residents of the Ivano-Frankivsk region in Western Ukraine were left without electricity and backup power supplies. Hackers managed to infiltrate the network and control center of the Prykarpattyeoblenergo power station in the region before compromising corporate networks threat actors were using spear-phishing emails with BlackEnergy malware.

The attack left 103 cities in the region completely cut off from the power grid, forcing Prykarpattyeoblenergo to manually turn the breakers back on. Once the power grid was shut down, threat actors not only carried out this operation, but also overloaded the call center with a high volume of calls, rendering it impossible for consumers to reach the power distribution station. The aftermath left an estimated 700,000 people in the dark, the most widespread of an attack at that time.

The author of this attack was reported to be Sandworm, a Russian state-sponsored group directly tied with the Kremlin. Sandworm, is also known by the military name of unit 74455, directly reporting to the GRU, the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. Other names given by cybersecurity researchers include Telebots, Voodoo Bear, and Iron Viking. This group is believed to be also responsible for the 2008 DDoS attacks in Georgia.

This was not the only attack that impacted the Ukrainian energy infrastructure. On December 17th, 2016 shortly before midnight, a second attack happened to interrupt the operation of the “Severnaya” substation of the energy company Ukrenergo. Consumers in the northern part of Kyiv and surrounding areas were left without electricity. As with the December 2015 attack, the suspected bad actor of this attack was the same as in 2015, Sandworm. However, in this attack, they leveraged another malware called Industroyer. This attack significantly less extensive than the previous attack, but in the wake of this Ukraine’s then-president Petro Poroshenko levied charges against Russia, accusing them of initiating a cyberwar against Ukraine.

On June 27, 2017, a large-scale destructive cyber operation was carried out against Ukrainian institutions and organizations. The “critical nodes” of the energy companies Ukrenergo, Kyivoblenergo, Dneproenergo, Zaporozhyeoblenergo, and the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant were directly attacked by bad actors utilizing NotPetya malware. This cyberattack was aimed at disrupting company websites and customer support systems, causing $10 billion in damage to local companies, and spreading to others all over the world.

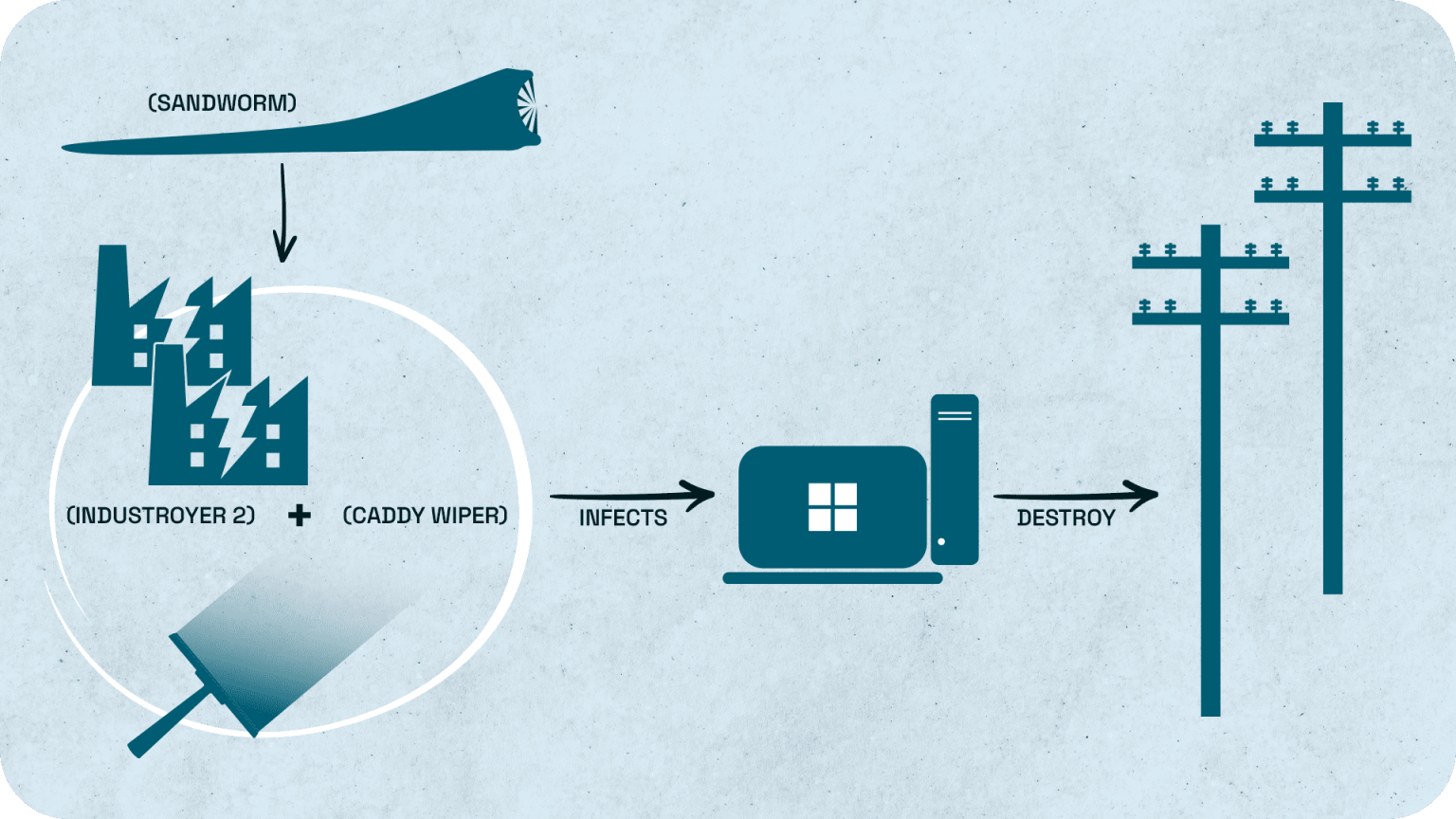

As the resulting war broke out in Ukraine on February 24th, 2022, the cyberattacks launched proved less effective. In April 2022, Sandworm attempted to deploy the Industroyer2 malware and Caddywiper against high-voltage electrical substations in Ukraine, with the intent to attack high-voltage electrical substations. However, the Computer Emergency Response Team of Ukraine (CERT-UA) claimed to have thwarted the attack. Analysts found out how Industroyer2 is a variant of Industroyer, the same malware first used in the attack against the Ukrainian power grid in 2016.

With the escalation of the military situation, the risks in cyberspace also continue to grow, with possible consequences on critical infrastructures are increasing exponentially.

Questions remain: Can the European Union address with these threats successfully? How can the region avoid the destruction of their infrastructure? What are specific weak points? How serious is the threat of information theft? The geopolitical situation in Ukraine is exposing the weakness of CEI, highlighting how even one small error, like an employee opening an attachment or an infected device connected to the network, can compromise the whole system.

Cyberattacks on banks and information structures are not new, but what happens if hackers try to break into critical infrastructures, such as nuclear power plants? In the past, there have been numerous attacks on nuclear facilities.

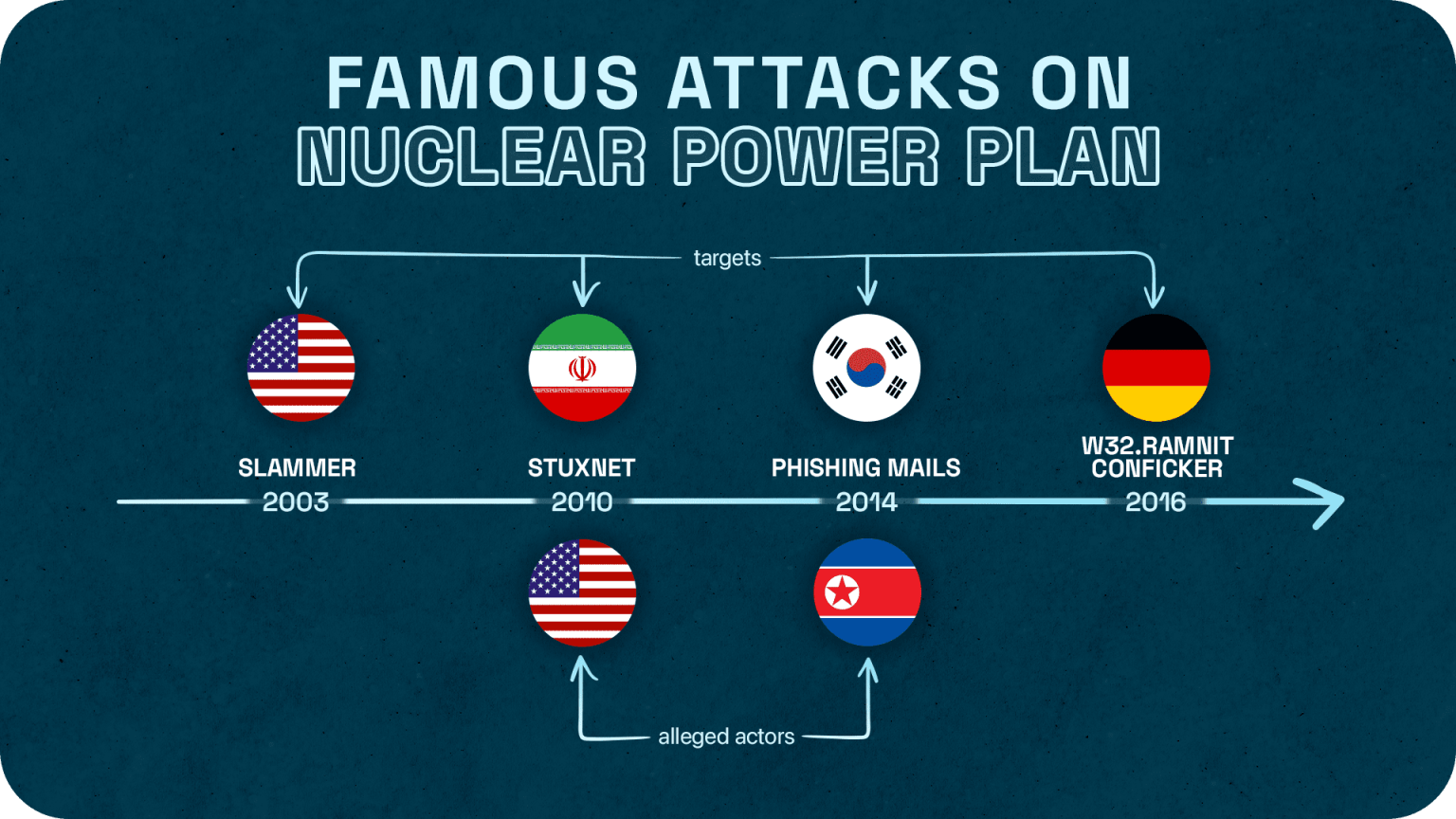

On January 25, 2003, in the United States, a worm known as “Slammer” attacked the corporate network of the Davis-Besse nuclear power plant in Oak Harbor, Ohio, rapidly spreading into the plant’s security monitoring and cooling systems. It was able to take the main computer offline, which lead to the failure of the power plant. During the aftermath of the attack, it took teams 6 hours to restore the systems to a functional standpoint.

In September 2010, about 200,000 industrial computer systems in Iran were infected with the malware Stuxnet. This attack led to the destruction of up to 1,000 uranium enrichment centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear facilities and halted the launch of the Bushehr nuclear power plant. According to experts, the cyberattack was targeting the Iranian nuclear infrastructure and set back the country’s nuclear program by at least two years. Iranian authorities accused US intelligence of being behind the attack.

In December 2014, in South Korea, hackers gained access to the internal network of Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Co., Ltd. (KHNP). The TA managed to penetrate the network after sending 5,986 phishing emails containing malicious codes to 3,571 employees of the nuclear plant operator. The attackers demanded the shutdown of the reactors at the Kori and Wolson nuclear power plants, and futher leaked some diagrams, internal instructions, and personal data on employees. South Korean authorities accused North Korea of the attack.

On April 27, 2016, in Germany, the computers of the Gundremmingen NPP (120 km from Munich) of the RWE energy company were infected with the W32, Ramnit, and Conficker viruses. Malicious software was found on 18 removable storage media in the computer system of Block B, inside data visualization software. The infection did not pose a threat to the safety of the nuclear power plant, however, since the control computers were not connected to the Internet.

The British Royal Institute of International Affairs, known as Chatham House, published a forecast detailing how nuclear power plants around the world could become an easy target for hackers. According to analysts, the infrastructure of these facilities is not prepared to protect itself from cyber threats. According to Chatham House, hackers, including those in the under the direction of sovereign nations, are stepping up to improve the accuracy of their attacks, while nuclear power plants are not keeping up with cyber defenses.

Cyberattacks against any one of the 103 nuclear power reactors, now operating in 13 of the 27 EU member states, could lead to catastrophic consequences if the personnel are not prepared to address them.

Future threats have the potential to be exacerbated by the interconnection of European infrastructure. Hacker groups will very likely exploit CEI’s vulnerabilities and its interdependency with other infrastructure sectors to threaten European countries by conducting cyberattacks against their energy infrastructure, impacting their economic system. Likely, cyber actors could also target the oil and gas pipeline infrastructure, dislocated into diverse European partners, harming European countries.

Analyzing this probable scenario, hacker groups could very likely disable a gas pipeline, likely crippling the gas imports, which would raise gas prices, threatening to damage the Italian economy and tax systems.

If cyber groups attack a hypothetical Italian/European oil & gas infrastructure in Tunisia this will likely temporarily suspend their activities in the area. This interruption could pose a rise in Tunisian employees’ distrust, furthering the likelihood of more riots and probable violent acts against infrastructure in the area. Increased violence and insecurity would drive to force managers to shut down its Tunisian units, further reducing the gas reserves supply, which could affect the Italian Net Export.

CONCLUSIONS

Taking all these points into consideration, we can clearly state how the overall infrastructure faces a massive risk, being far too interconnected and with too little preparedness to face a possible attack at the current time. The European countries should prepare a plan to avoid a probable spillover and, overall, increase the “cyber education” of all the workers involved in all aspects of critical energy infrastructure. A seemingly minute mistake could lead to unimaginable problems and risks for the civil society. The European Union should drastically increase its cyber defense budget and create a mutual support system, as the infrastructure is so densely interconnected.

Furthermore, it’s highly recommended to European countries strengthen their relations with their partners by reinforcing their anti-terrorism and counter-terrorism alliances, especially in terms of cyber-terrorism, and by developing a shared special task force to protect their energetic information security and prevent cybercriminals penetrations.